Remembering Nepal’s conservation heroes

That night in Taplejung, we sang and danced to the tune of Sorha Barse Umera Ma. It was my conservation guru Chandra Gurung’s favourite song, and one he sang during many occasions.

That song still brings back memories of the night 15 years ago as I sing it in every staff retreat to pay tribute to my mentor. The pain of loss is still palpable.

We celebrated, but it was short-lived. Little did I know that 24 hours later I would be hiking all night with Ang Phuri Sherpa and a rescue team to Ghunsa to find the crash site, after bad weather forced our search helicopter to drop us in Pholey.

It had been rainy in Ghunsa on 23 September 2006, as the Mi-8 helicopter took off and disappeared into the clouds. I was supposed to be on it, but had to make space for the dignitaries who had come for the handover ceremony of the Kangchenjunga Conservation Area (KCA) to the community.

Twenty-four people died in that tragedy this week 15 years ago, among them Nepal’s conservation heroes: Harka Gurung, veteran geographer and planner; Chandra Gurung who designed the model of using tourism income to pay for conservation; Mingma Norbu Sherpa, who helped establish the Annapurna Conservation Area; Tirthman Maskey, who paved the way for people and parks to coexist. Nepal also lost Forest Minister Gopal Rai, Secretary Damodar Parajuli, and Director Generals Sharad K Rai and Narayan P Paudel. Also on board was the first Chair of the KCA Management Committee, Dawa Tshering Sherpa.

The shock of the deaths posed a pressing question: were Nepal’s achievements in conservation now in jeopardy? The model of participatory conservation pioneered in Nepal was an example to the world, but could the path-breaking work of these visionaries be sustained?

Fifteen years on, looking at the accomplishments since, we can proudly say that the country has honoured those leading lights of Nepal’s conservation movement by carrying on their work, and come out even stronger.

We have witnessed a remarkable shift in various facets of conservation in Nepal: from the recovery of species numbers to the expansion of protected areas systems with growing participation of people from all walks of life.

Nepal’s tiger population has crossed 235, indicating a dramatic increase from 121 in 2009. The number of rhinos increased from 435 in 2008 to 645 in 2015, with zero rhino poaching for the first time since 2011. Snow leopard conservation and research has advanced, with Nepal now holding the fifth largest population among 12 snow leopard range states.

There have been similar successes among other species, including blue sheep, Himalayan tahr, gaur and gharial. The species recovery of rhinos, blackbuck, wild water buffalo in their former ranges are other important milestones of our conservation journey.

After KAC, Nepal has added three more protected area systems: Gauri-Shankar Conservation Area, Api Nampa Conservation Area, Banke National Park – covering 4,632square km across two landscapes, Kailash and Chitwan-Annapurna.

These conservation initiatives have placed emphasis on ensuring equal benefits to communities promoting a harmonious existence between humans and wildlife. The community-based conservation initiatives have been critical in protecting species as well as ensuring a sustainable future for people living in and near wilderness areas.

While the sudden loss of so many professionals put a dent on Nepal’s environmental movement, their legacy has continued with a new generation of committed specialists who were trained and mentored by them. This new crop of young conservationists received scholarships established in the memory of the pioneers who died 15 years ago. They have gone on to do exemplary field work, and are now in key decision-making positions in Nepal to guide future conservation efforts.

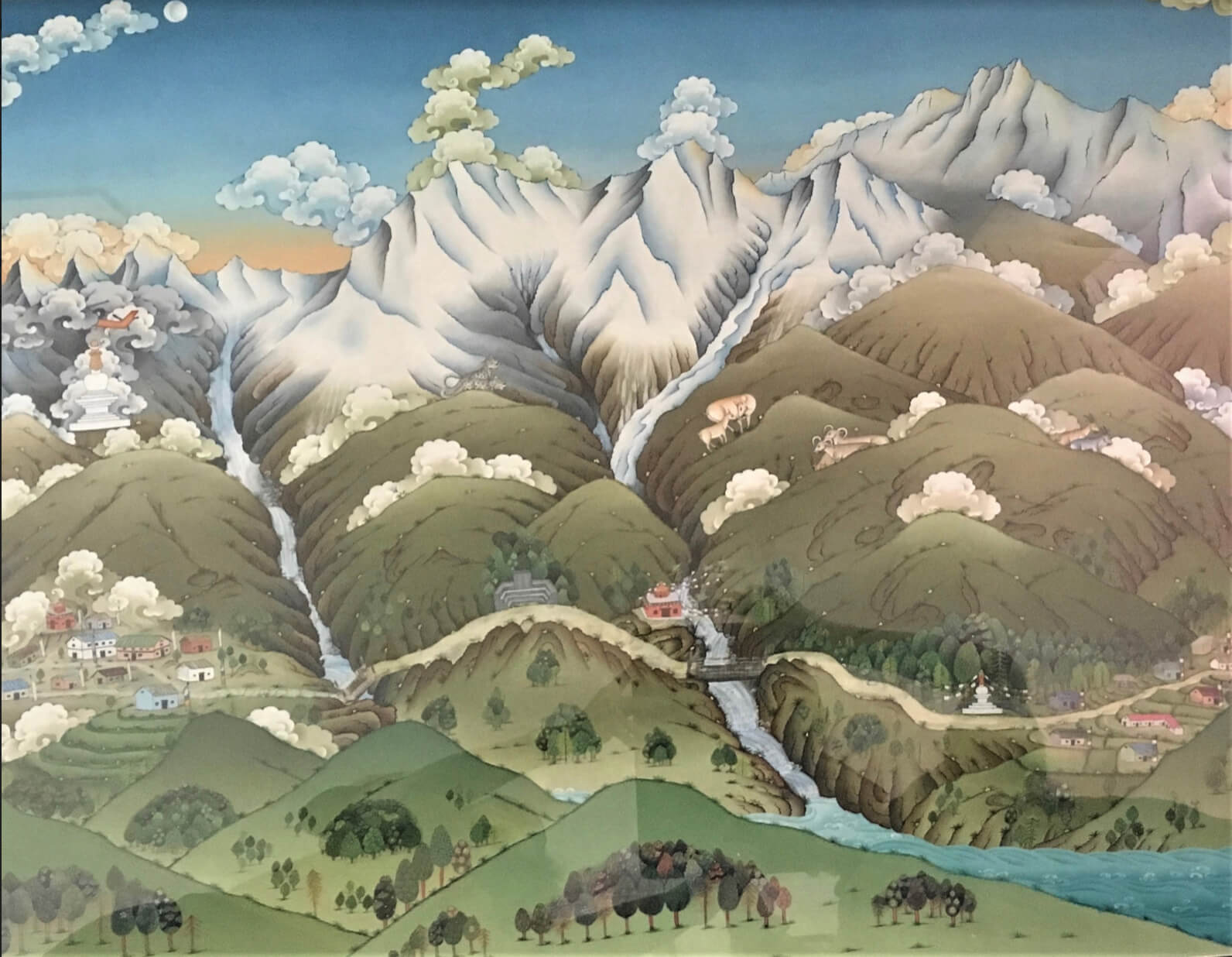

In Kangchenjunga itself, the KCA has led by example for 15 years, presenting a strong case for participatory conservation where the local community is entrusted with the stewardship of the natural and culture resources of the region below the world’s third-highest mountain.

The concept of participatory conservation has been around since mid-1980s after Mingma Sherpa and Chandra Gurung first introduced it in the Annapurna Conservation Area followed by the Manaslu Conservation Area. Now, the KCA has gained recognition across Asia as an exemplary model in championing this approach.

There were a slew of underlying factors that laid the basis for KCA’s success – primary among them were concrete legal, institutional and financial mechanisms.

The KCA project was launched in March 1998 by the government in partnership with WWF Nepal to address both the livelihood needs of local people and biodiversity conservation. In the lead-up to the handover of this protected area in 2006, numerous legal and policy instruments were put in place, including conservation area management regulations and plans.

A community-based Kangchenjunga Conservation Area Management Council (KCAMC) was formed, and entrusted with running the KCA with full authority to take care of the region’s natural resources. A community-based women’s group was also formed and trained, and now has 33% representation in KCAMC.

We can take this as an example of how integrating communities into conservation efforts can yield multipronged benefits. To date, 35 mother’s groups have provided 206 scholarships to socio-economically excluded girls, many of whom have grown up to be professionals working at KCA and elsewhere.

For conservationists, the handover of KCA in 2006 was a significant milestone, it also ended up being an unimaginable tragedy and setback. Merely 12 hours after celebrating the transfer to the community in Taplejung, and soon after taking off from Ghunsa, the helicopter carrying Nepal’s top conservationists flew into a cliff hidden by cloud. Ever since, 23 September has been marked as Nepal’s National Conservation Day in memory of these Conservation Heroes.

Chungla Sherpa, a former scholarship recipient and now a ranger at the Forest Research and Training Center in Pokhara says, “The Mingma Norbu Sherpa Memorial Scholarship had a profound impact on my life. It built my future, and I hope that I will be able to follow the footsteps of the conservation heroes who made this possible. I hope that I can someday give back to others.”

The leaders continue to make a positive impact on Nepal and the world long after their departure. We may have lost our heroes on that fateful day, but their work has carried on through a new generation which was given the opportunity for the best conservation education through scholarships created in their memory. I feel fortunate and grateful to have been one of them.

Now, we need to pass the torch to yet another generation to help preserve our natural heritage, just like our predecessors once did. Fifteen years down the line, Nepal has taken great strides in conservation despite the tragedy, and despite facing multiple challenges since.

Let us mark this day with a renewed commitment to the goals set by our conservation pioneers, so we can overcome obstacles that lie ahead as we grapple with the pandemic and its aftermath.

Ghana S Gurung is the Country Representative of WWF in Nepal and Snow Leopard Champion for the Global WWF Network. The views expressed here are personal.