Power to the periphery

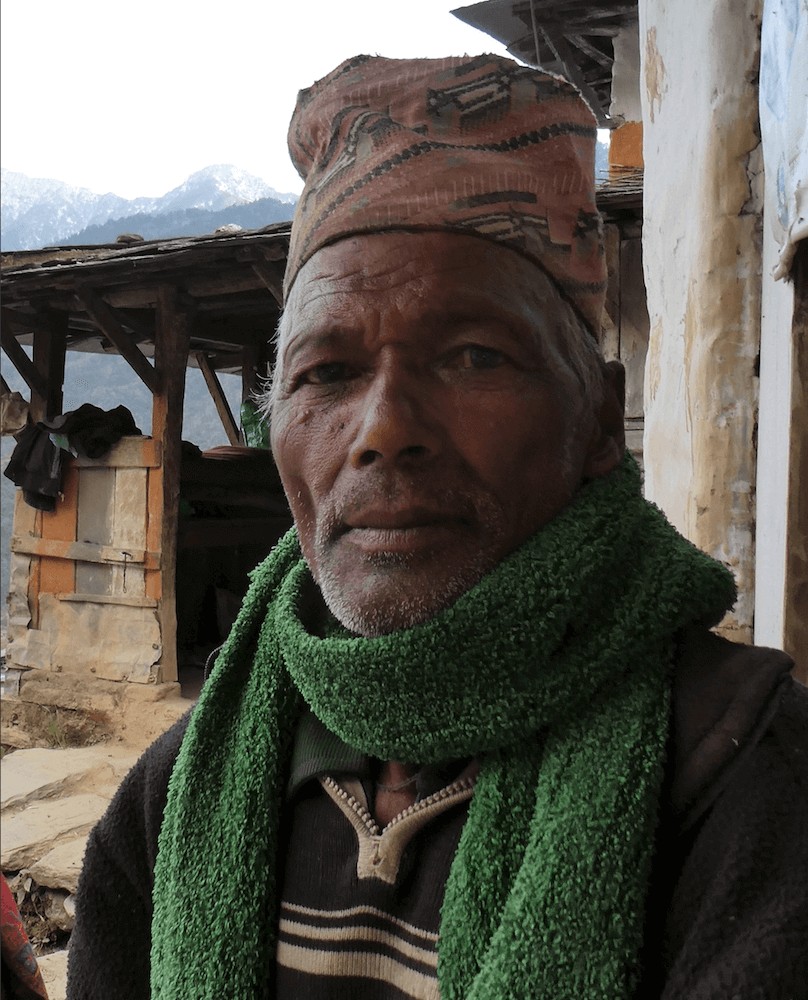

Bal Bir Biswakarma from the village of Lulang at the lap of Mt Dhaulagiri in Central Nepal is a 68-year-old subsistence farmer, descendants of metal smiths who settled here centuries ago to smelt copper ore.

When the copper ran out, he became a high altitude porter, summiting Mt Lhotse and even rock climbing in Wyoming in the United States. But, as Joy Stephens writes in her travelogue most of his life Bal Bir Biswakarma has been living hand-to-mouth in this Dalit village high up in the mountains.

Since 2017, Lulang is a part of Dhaulagiri Municipality and elected Thamsara Pun as mayor who took the revolutionary step of moving the headquarter from the traditional power centre of Takam to Muna village to make it better accessible to the region’s indigenous and Dalit populations.

In the past five years, villagers have begun to see improvements in healthcare, education and jobs, thanks to political devolution gained through Nepal’s new federal structure. Pun is looking forward to fast-tracked local elections on 18 May, and the chance to serve five more years.

This is what federalism means in practice: giving voice to the voiceless, letting under-served communities take charge so they can better take care of themselves. Dhaulagiri Municipality is also a reminder to the squabbling political class in faraway Kathmandu, some of whom have prematurely declared federalism dead without even letting it prove its worth.

Excitement about local elections is already palpable across rural Nepal, but a cynical and pessimistic political class in the national capital does not want to let go of power and resources. In fact, despite a federal Constitution, political decision-making is more centralised than ever before.

While the rights of local governments are enshrined in the Constitution, it is not followed in the spirit with access to resources for them to actually perform.

“Federalism is the sum total of everything we Nepalis have gone through, from various governing structures to the Maoist conflict, the Madhes Movement and everything in between,” explains Khimlal Devkota, recently elected to the National Assembly.

“Federalism stands for stability, development and devolution and we had high expectations, expecting quick results,” he adds. “In some ways we have succeeded, people don’t have to rely on Kathmandu for everything. But the centre is still involved in everything from hydropower plants to erecting view towers.”

The 2015 Constitution devolved rights to local and sub-national governments, but the necessary laws were not in place until after elections. This meant a confusing transition regarding jurisdiction which threatened to undermine past gains in areas like community forestry, public health and education.

“Coordination between the governments, vertical and horizontal, is a pillar of federalism and so is functional demarcation,” says Balananda Paudel who headed the Local Bodies Restructuring Commission. “Our laws are riddled with lack of clarity in some places and elsewhere there is a problem of overlapping functions for different levels of government.”

This results in a perpetual blame-game between different levels of government, and a lack of accountability. Federalism, therefore, is still work in progress and this year’s series of elections will hopefully result in greater devolution.

One of the reasons federalism got a bad name is that in the past years, it also decentralised corruption. Of the 753 local governments, one-third have elected chairs and mayors who are contractors and have awarded themselves sand-mining, road-building and quarrying contracts.

Which is why upcoming local elections are even more important -- to reward elected municipal governments who have worked for the people with another five-year term and reject those who did not.

This might also be a time to question the purpose of retaining a parallel power structure composed of the District Administrations and the Chief District Officers. Its job of issuing citizenship papers and passports allows this unelected office of centralised bureaucrats to wield extraordinary power over ordinary people.

Federalism has also multiplied central-level politics by seven. Bagmati Province recently set a new record with 70 mini-ministries in Hetauda to allow the coalition to keep power. Much of the last five years were wasted in endless debates about demarcation of provincial boundaries and designating capitals. It took four years for Madhes Province to get its name, and Province 1 is still just a number.

“We have made some headway in formulating laws and regulations, now we must bring it into practice, improving staffing for service delivery at local levels and promoting better coordination between and within levels by activating intergovernmental relations,” says Balananda Paudel.

Just as democracy is only as effective as politicians, federalism too will only function if it follows the true spirit of devolution of power and resources to the periphery. It needs political will at the centre to provide technical and financial support – something we have not seen in the last five years.

Says Khimlal Devkota: “Citizens should be placed at the centre of all decision making. This can be done only by nurturing and strengthening federal practice.”

writer

Sonia Awale is Executive Editor of Nepali Times where she also serves as the health, science and environment correspondent. She has extensively covered the climate crisis, disaster preparedness, development and public health -- looking at their political and economic interlinkages. Sonia is a graduate of public health, and has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Hong Kong.