Nature without borders

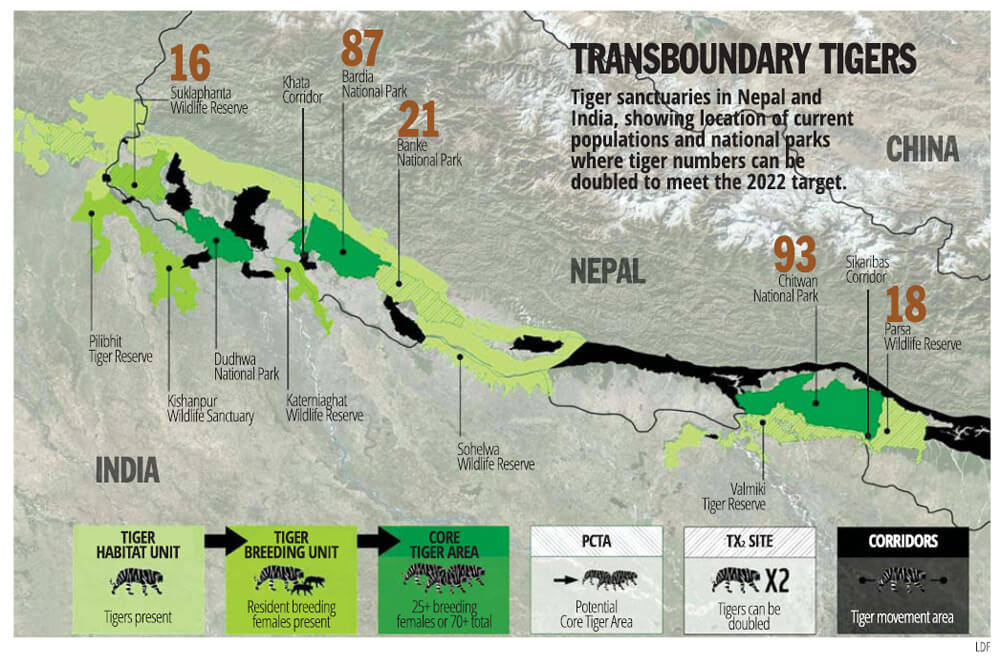

Parsa National Park has 18 adult tigers today, up from seven in 2013. In Chitwan, tiger numbers have increased from 91 to 93. In Banke National Park it went up from 4 to 21, and from 50 to 87 in Bardiya National Park.

Across the border in India, there have been similar increases. Here in the Valmiki Tiger Reserve, the number of big cats has gone up, but the exact count will be known after an ongoing Indian tiger census is completed. There has been a similar increase in Katarniyaghat Wildlife Reserve bordering Nepal. However, greater tiger populations along the India-Nepal border have increased the threat of cross-border poaching and human-wildlife conflict.

“Our conservation efforts will succeed only if we see Chitwan, Parsa and Valmiki Tiger Reserve not as separate territories but as a complex,” says Ajay Sinha, Range Officer of the Valmiki Tiger Reserve in Bihar. “We are collaborating with Nepal to ensure that we provide animals what they need, and do not duplicate efforts. We communicate almost on a daily basis, bypassing bureaucratic procedures that would take months.”

Read also:

It's a jungle out there, Kunda Dixit

Naturally Nepal, Editorial

Both India and Nepal are now getting communities on both sides of the border involved in conservation. The two governments, with the help of World Wildlife Fund (WWF), have installed solar-electric fences to stop animals from entering villages, distributed biogas and LPG gas to reduce use of firewood, promoted livestock management to reduce encroachment into forests, and formed Rapid Rescue Teams (RRT) and Community-Based Anti-Poaching Units (CBAPU).

Last year, when several rhinos from Chitwan were swept into India by a flood, residents of Binwaliya village in Bihar rescued some and returned them to Nepal. Recalls one of the villagers, Sanjay Kumar: “The rhino was in the field, and we called the Forest Department which tranquilised it and sent it back. Previously, if we saw wild animals in our villages, we would try to shoo it away, injure it, or even kill it.”

Since Nepal committed to doubling its tiger numbers, it began habitat management, protection, and community engagement, many of which have to be implemented side by side with India. Along the border in Chitwan and Parsa alongside India’s Valmiki Tiger Reserve in India, there are Nepal Army guard posts every 5-10 kilometers to stop cross-border poaching. All three sanctuaries have worked together to improve grasslands to attract prey for the growing number of tigers.

Read also:

How many tigers in Nepal?, Kunda Dixit

Where forests have depleted along the Nepal India border, local communities have helped rehabilitate many forest corridors. Shikaribas corridor in Parsa and Khata corridor in Bardia have been extremely important in facilitating the movement of animal and growing their numbers. “Animals need not just food, but also open space for movement, and sheltered space for cover,” explains Bharat Gotame of WWF Nepal. “Tigers can travel 300 km over two days in serach of prey, and elephants have migratory routes. So, their habitat should not be fragmented.”

But the impact of such fragmentation is already visible in Nepal, where the East-West Highway cuts through the Banke and Bardia National Parks and Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve. Last year alone, Bardia National Park lost over 60 wild animals to road kill, most of them deer. The new feeder roads that run parallel to the Indian border dissects the Chitwan-Parsa-Valmiki Complex.

“We need Smart Green Infrastructure with under and overpasses so that increasing connectivity does not endanger wildlife,” says Warden Ashok Bhandari at Bardia National Park.

Haribhadra Acharya at Parsa National Park agrees, adding that since tigers are at the top of the food chain, more tigers means a healthier eco-system. “A healthy population of tigers means that there is also a healthy population of deer and other prey, and the variety of plants that these herbivores feed on,” Acharya explains.

Read also:

Sun striped shadows, Lisa Choegyal

Clouded future for the Clouded Leopard, Yadav Ghimirey

The success of trans-boundary conservation and the increase in wildlife has brought another, more immediate threat to the very communities that protect them. Human-wildlife conflict has increased as wild elephants, wild boar and monkeys regularly raid farms. Leopards and tigers kill livestock and even humans. Parsa National Park has attempted to solve this problem by relocating two villages that were inside the park. However, several villages that line the Indian border and are sandwiched between forests of India and Nepal, are threatened by wildlife.

One of them is Kanchhi Lama of Subarnapur at the edge of the Parsa National Park, who has fortified her goat shed with metal nets to protect animals from leopards. But she adds: “We hear leopards growling at night, and we are scared to go out.”

In the west, the Khata Corridor provides the only link between Bardia National Park and India’s Katarniyaghat Wildlife Reserve, and several villages have regular encounters with tigers and elephants. Bhagraiya has 70 households and is surrounded by forests on three sides, and some villagers say it is now getting too dangerous to live there, and would like to be relocated.

Laxmi Chand of Bhagraiya village survived an encounter with a leopard in her goat-shed recently, and says: “We have stopped planting crops in our fields near the forest. What is the point? Wild animals will destroy it all.”

Read also:

No tiger, no mountain, Kunda Dixit

Tigerman, Lisa Choegyal