Nepalis stranded in the Maldives

Ninety percent of Nepal’s overseas contract workers are in West Asia and Malaysia, but there are other countries like the Maldives where the estimated 5-10,000 Nepalis employed in the tourism industry have been affected by the global pandemic.

The resorts of this atoll archipelago nation have been increasingly popular for Nepali workers, who have built a strong reputation for work ethics there. Last year alone 2,000 Nepali workers left of the Maldives, nearly four times more than in 2015, to work in hotels and as housemaids.

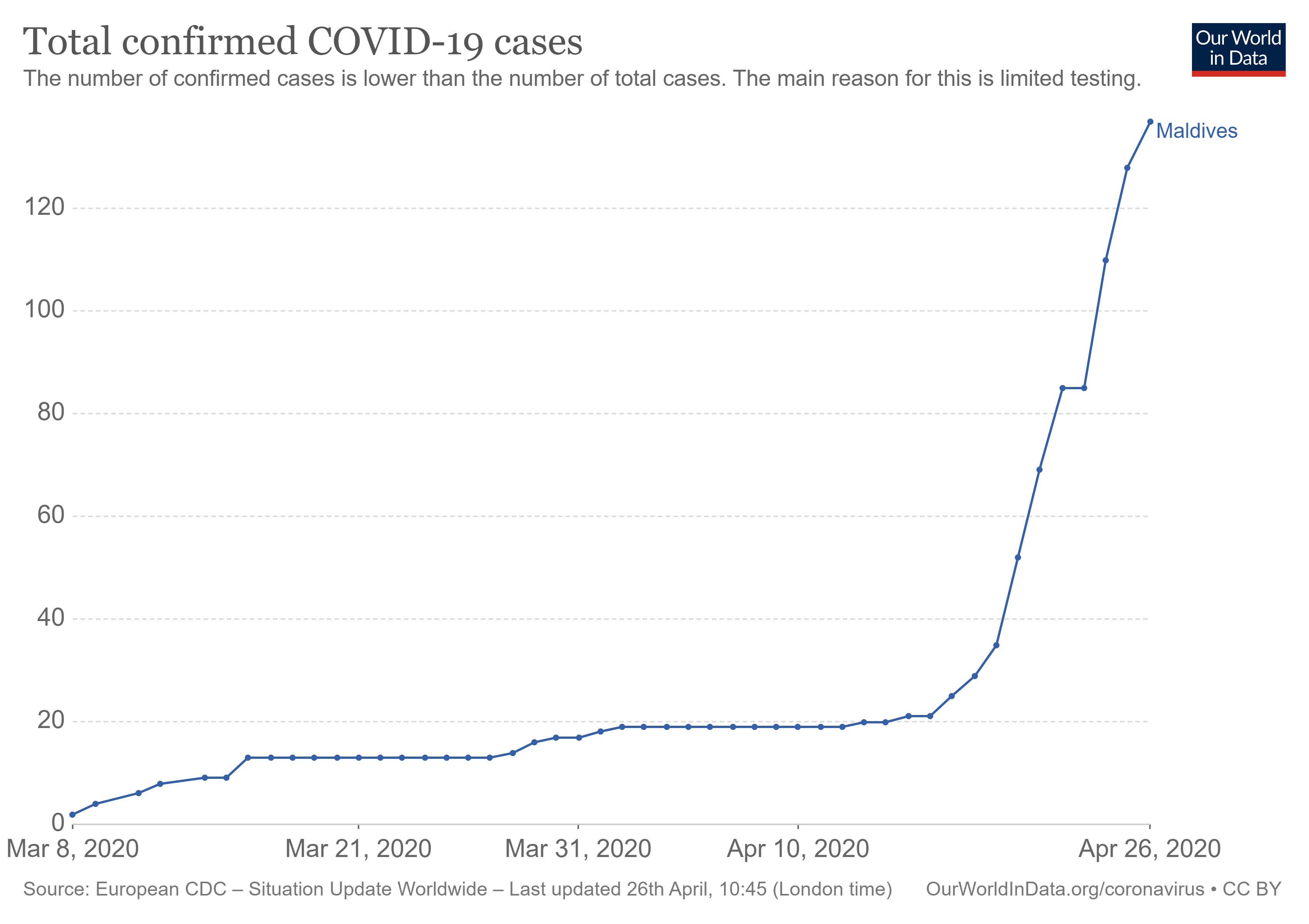

But some of these jobs are in jeopardy because of the pandemic. Of the 191 confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Maldives, over 102 are foreigners including 84 Bangladeshis and 10 Indians. Nepalis have so far been spared, but there is a fear they could be vulnerable because of cramped living conditions.

“Overall, Nepalis have created a favorable impression in the Maldives, but tourism has collapsed because of the coronavirus and Nepali workers have been affected,” says Rita, who has been working in the Maldives for four years, and only wanted her first name used.

Similar to Nepal, Maldives also set a target for attracting 2 million tourists in 2020, in what seemed like an achievable goal given that 1.7 million tourists visited the country in the preceding year. Tourism makes up two-thirds of the GDP of the Maldives and brought in $2.5 billion last year.

Maldives has a per capita GDP of $10,330 – highest in the region and ten times higher than Nepal. But the World Bank predicts that it is the South Asian country that will be most impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. The Maldivian government hopes to start issuing visas on arrival by July, but even in the best-case scenario it expects arrivals to drop by half in 2020.

A Nepali worker at a luxury resort told us over the phone that the Maldivian government has assured foreign workers that they will be treated on par with locals, and indeed employers were providing food and accommodation to them in the resorts which is a huge relief.

However, he added: “But some staff are not getting paid, while others are only getting partial salary and this has worried some workers.”

Some hotels have told workers they should go home on unpaid leave until the tourism industry bounces back. In a survey by the Nepali community, 319 have expressed the desire to go back to Nepal paying for their own tickets. But there may be more who want to return if the Nepal government eases travel restrictions.

“We came here to work. Without tourism, there is no work here. Without work, there is no point staying here,” says Rita, who is getting half her salary and spends the day surfing the net. “But I am also aware that my situation could have been much worse.”

Another Nepali resort worker agrees: “We have access to room and board and 30% of our salary. Why should we stay here when we don’t have work and it is evident that tourism is going to remain affected for a while?”

Workers are worried that things will get worse in the Maldives if tourism is affected for many more months with disruptions in food supplies. They are far away from Malé and say it may be difficult get transportation if they get sick.

The focus in the Maldives is mostly on Bangladeshis who number 100,000 and make up a bulk of migrant workers there. They are mostly in Malé, and because there is a higher risk of being infected the government is relocating them to decongest the city. The Bangladesh government recently sent 100 tons of equipment and 10 medical personnel to treat its nationals.

Seven Nepalis working as security guards at a resort who were sent to Malé, have had to fend for themselves in an expensive city. One of them, who identified himself as Ram, told us over the phone: “It costs $50 a night to stay here, and the Nepali community has been helping out with meals. But how long can we go on? What if the lockdown is prolonged?”

Attempts to reach the Nepal Embassy in Colombo has not led to any solution. Nepali community leaders in Malé say that the need for a resident embassy or at least a consulate is felt most acutely during a crisis like this.

It is likely that countries like Maldives, Seychelles and Mauritius which have Nepali workers in the service industry will not get the priority for phased repatriation once the lockdown is lifted because of the comparatively smaller numbers involved. But while they wait to return, community leaders say it is important to ensure that no Nepali goes hungry, is homeless or without access to health care.

Shares Hari: “When workers eventually return to Nepal, many will have had worked in high-end resorts. We many things to learn from Maldives, especially in luxury tourism. There is a lot of knowhow we can transfer once things get back to normal.”