Nepal sees spike in suicides during pandemic

- Two years ago after going through a bad relationship, a 36-year-old Kathmandu-based doctor started getting suicidal thoughts. During the long months of lockdown, he would be on the rooftop and imagine jumping off to end it all. But before long he realised that he was causing self-harm, and sought help. He was diagnosed with depression, eight months into treatment he is rid of suicidal thoughts and is back to his outgoing ways.

- The bubbly young woman used to be the life of every party, but few of her friends and relatives realised what was going on inside her mind. As the pandemic hit, she started having violent thoughts about harming others and herself. The 22-year-old tried to deal with it herself, but two months ago she sought help from a mental health doctor. She was diagnosed with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and started treatment. Looking back, she advises others to also seek professional help in time.

- The young woman felt worthless, lacked confidence, avoided crowds and had self-inflicted cuts on her arm. Her inability to come in terms with her sexuality aggravated her sense of insecurity. When the pandemic foiled her plans, she blamed everything on herself, she felt irritated and uncertain, stopped attending virtual classes and her eating habits changed. She finally sought help for her depression and she is now under regular psychiatric counselling and medications. Grounding exercises in particular have helped her overcome self-harm and feelings of inadequacy. “I am okay now,” she says.

As the pandemic turns lives upside down, there has also been a global outbreak of mental health disorders, and Nepal has reported a rise in suicides. However, as these cases show, professional counselling and medication can save lives.

Recoveries rarely make news, only suicides do.

“Most of my patients who attempted suicide have gone on to lead normal lives after they get treatment, and oftentimes they look back to their mental health crisis as nothing more than a lapse of judgment,” says psychiatrist and researcher Rishav Koirala.

There has been a sharp rise in suicides in Nepal since the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020 and subsequent lockdowns. Nepal Police data shows that in the last 12 months, there have been 7,141 reported deaths due to suicides nationwide, up from 6,252 the year before.

Do not shy away from seeking help. If you, or anyone you know, would like to speak to a trained mental health professional, please contact:

TUTH Suicide Hotline: 9840021600

Transcultural Psychosocial Organisation-Nepal Crisis Hotline: 1660 0102005

Mental Health Helpline Nepal: 1660 0133666

Centre for Mental Health and Counselling Nepal Toll-free: 16600185080, Hotline: 1145

Koshish Toll-free helpline: 166001-22322 (Bagmati Province)

Patan Hospital Helpline: 9813476123

National Suicide Prevention helpline operated by Mental Hospital Lagankhel and TPO: 1166

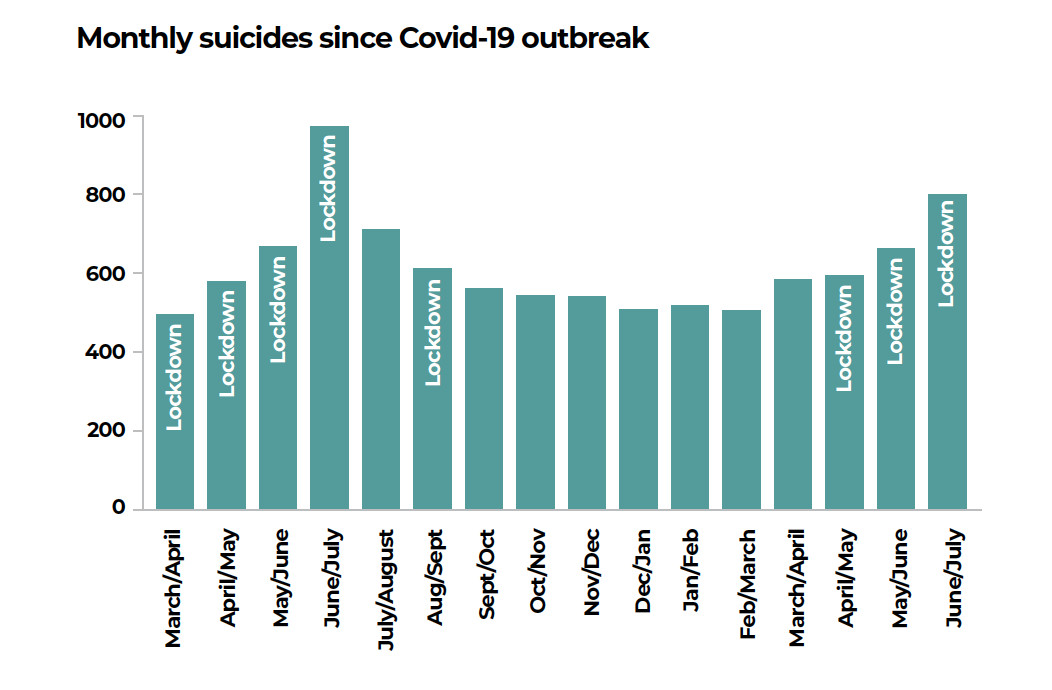

In a survey last year, Transcultural Psychosocial Organisation (TPO) Nepal which works with mental health compared five years of suicide data for March-July to see if there was any change during the lockdowns in 2020 and 2021.

The results are revealing: suicides have been increasing steadily at an average rate of 8.5% every year, but it spurted to 19.4% in the first four months of the lockdown. Researchers also conducted key informant interviews across Nepal, who reported witnessing an increase in suicidal behaviours in the community as well as health facilities.

“We now have both quantitative and qualitative evidence that mental health problems have increased following the pandemic,” says TPO Nepal’s executive director Kamal Gautam. “And given that the majority of suicides are caused by psychological problems, we can say that Covid-19 has significantly contributed to its increase.”

Mental health professionals have long been warning of an epidemic of psychological disorders following the Covid-19 crisis. They have reported an increase in anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), hypochondria, obsessive disorders and psychotic symptoms among the general population in the last two years.

Economic collapse, job loss and slashed income due to the pandemic as well as increased domestic and sexual violence and added workload during the lockdowns have all acted as contributing factors. In addition, those afflicted do not have normal social interactions that used to be a safety valve during more normal times.

Moreover, many patients on treatment and medication have relapsed due to the limited access to health services, counselling and psychotropic drugs during the pandemic, and in many cases because of Covid phobia.

Up to 80% of suicides have mental health disorders as an underlying cause. A significant portion of cases are also a result of impulsive behaviour.

Experts agree that the official numbers on suicides are vastly underestimated due to a lack of suicide registry. Official figures are based solely on police data and post-mortems, and because of stigma associated with mental health, many families also often refrain from revealing the actual cause of death.

Official records also do not take into account suicides of Nepali migrant workers overseas, mainly Malaysia and South Korea. Similarly, suicides among those in the LGBTIQ community who have lost their limited sources of livelihood during the pandemic have been largely neglected.

“Reported cases alone are not conclusive, but given that we now have a year and a half long trend and data, we have seen a significant increase in mental health disorders, and can assume that pandemic has played a crucial part in the rise in the number of suicides,” adds Rishav Koirala.

More than 700,000 people die by suicide every year around the world, that is one in every 100 deaths -- more than HIV, malaria, breast cancer, or war and homicide. And for every suicide, there are many more who make attempts to end their lives.

Nepal is among the countries with the highest suicide rates in the world and consistently ranks within the WHO’s top 10 list. The Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC)’s National Mental Health Survey published earlier this year found the prevalence of suicidality (current suicidal thoughts, lifetime suicidal attempt and future likelihood of suicidal thoughts) to be high at 7.2% among Nepalis.

The first of its kind survey in Nepal interviewed 15,088 participants and was carried out before the pandemic from January 2019 to January 2020. The study revealed that 10% of Nepal’s adult population had mental health problems in their lifetime with 4.3% experiencing some disorders at present.

Mood disorders and neurotic and stress-related disorders were among the most common psychological problems among Nepalis. The prevalence of lifetime disorders was found the highest in Province 1 (13.9%), in the age group 40-49 years (13.3%) and among males (12.4%). As for current disorders, Bagmati scored the highest (5.9%) as well as those in the age group 40-49 years (6.3%) and females (5.1%).

These figures correlate with Nepal’s suicide data of the past five years. Despite fewer attempts, men accounted for 57% of total suicides, against 43% of women. Among minors, however, more girls died by suicide, which experts ascribe to possible victimisation and a higher prevalence of borderline personality disorder among younger females.

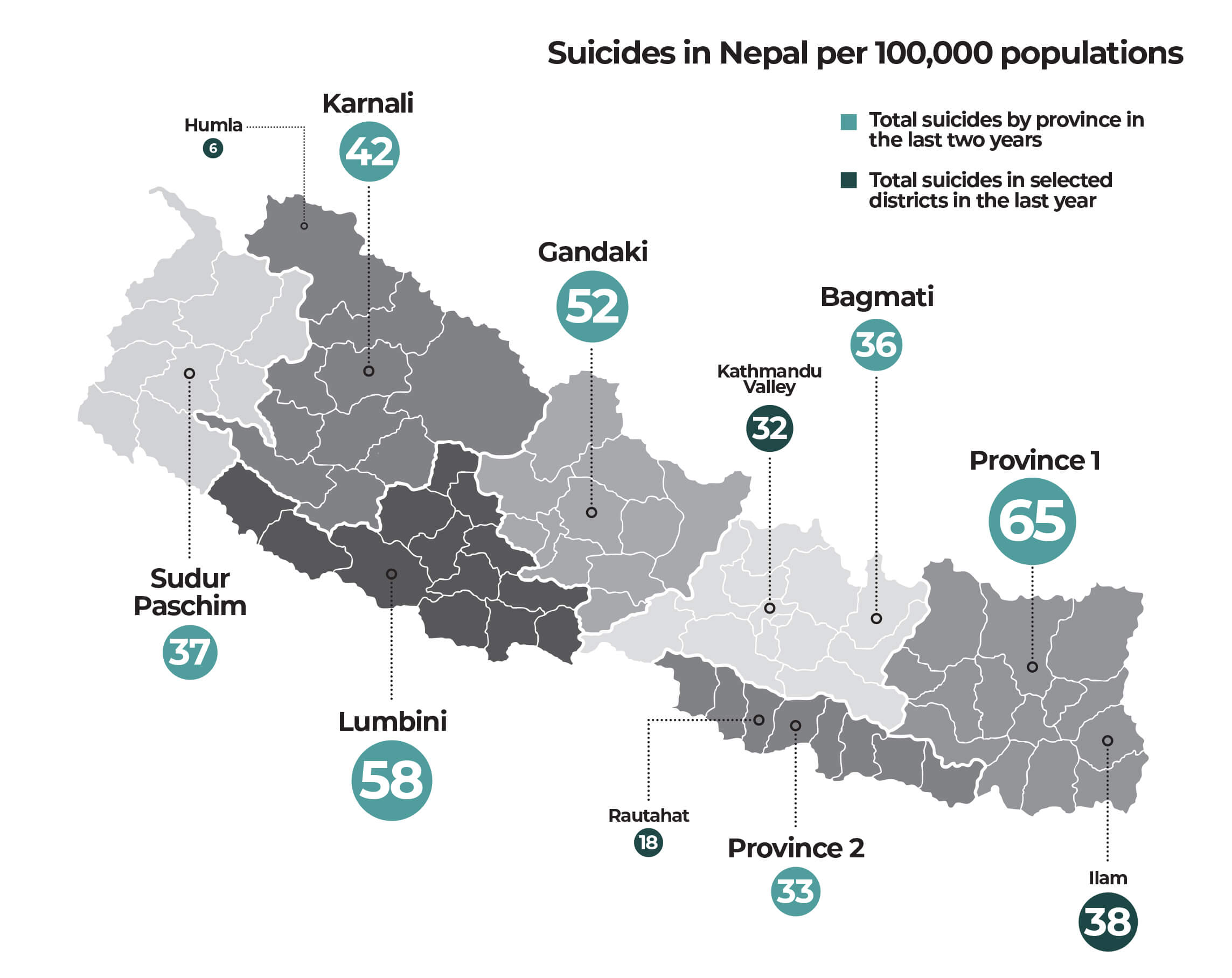

Suicide deaths are also disproportionately distributed across Nepal with Province 1 recording 65 deaths per 100,000 populations. Lumbini and Gandaki follow closely with 58 and 52 per 100,000 respectively. Traditionally neglected by the state and economically disadvantaged Karnali, Far West and Province 2 regions have lower suicide rates.

More people are dying of suicides in urban centres such as Kathmandu Valley and Ilam district, which reported 32 and 38 suicide deaths respectively per 100,000 populations last year against Rautahat’s 18 and Humla’s 6.

This is in direct contrast with the global trends where 77% of suicides occur in low and middle-income countries. Unemployment and poor economic condition have long been associated with a high risk of suicides, but only up to a certain point, as proven by recent data. Japan, South Korea and Hungary with their higher per capita GDPs have some of the highest suicide rates in the world.

“Poorer nations have weaker education and health systems, which translates into delayed or even lack of diagnosis but poverty is not a sole factor for suicides,” says Kamal Gautam. “Suicide is complex and there are multiple factors at play which means a linear approach to prevention would be incomplete, it needs an integrated approach.”

Addressing underlying mental health disorders is the most effective way to prevent suicides. This means increased awareness and education about psychological disorders, which in turn can help reduce societal stigma. An introduction to and discussion on mental health in the school curriculum can further sensitise the public.

In addition to medication and counselling, societal structure and family dynamics is an important support system for individuals suffering from psychosis, trauma and depression. Telemedicine in particular has been essential in preventing self-harm during the pandemic-induced restrictions but mental health services need to be scaled up across the country.

On the other hand, a strict regulation must be implemented on the availability of pesticides, an easy means of suicide for many. Access to alcoholic products must also be supervised with Nepalis known to self-medicate to cope with stress and trauma, in turn increasing the risk of self-harm and suicide.

But most of all, analysing suicide attempts can be a powerful tool for prevention. On average, there are six attempts behind every suicide. Up to 80% of people with suicidal ideation reveal their intention to either a family member, friends or their doctors within a month before their attempt.

“We forget that even before the pandemic suicide rates were very high in Nepal and while the pandemic might have added to the problem, the figures alone don’t mean anything if we fail to also study suicide attempts to find a stronger link between the prevalence and the contributing factors,” says Rabi Shakya, psychiatrist and director of Patan Academy of Health Sciences.

He adds: “Historically, there have been more suicides after than during the crisis due to the long-term socioeconomic impacts. So we must start preparing for the pandemic of mental health problems including suicides post-Covid. Our health care workers must be trained and fanned out across the country.”

Nepalis are not new to mental health problems induced by a crisis. The 10-year-long Maoist insurgency killed 17,000 people but many more continue to suffer from PTSD, depression, anxiety and distress. A 2017 report published in the journal Lancet found as high as 37.5% of the general public had some form of psychological disorder.

The 2015 earthquake further added to Nepal’s epidemic of mental disorders. Survivors who had narrow escapes or lost family members reported increased panic attacks, anxiety and trauma.

But conflicts, disasters and pandemics have shined a light on mental health with an increased national and foreign investment in prevention and management. With larger chunks of the population impacted, there is now more acceptance and the field is starting to get the priority it warrants.

Says Rishav Koirala, WHO focal person for mental health post-2015 earthquake: “The best way to prevent suicides is to address underlying psychological disorders and crises, despite adding to the burden has helped normalise them because many more people can now relate and understand that they are treatable.”

writer

Sonia Awale is Executive Editor of Nepali Times where she also serves as the health, science and environment correspondent. She has extensively covered the climate crisis, disaster preparedness, development and public health -- looking at their political and economic interlinkages. Sonia is a graduate of public health, and has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Hong Kong.