Putting Nepal on the right track

A train network will generate jobs in construction and operation, bring efficiency and connectivity

Imagine it is the year 2070 AD. You board a train in Janakpur at 7:37AM, enjoy scenic views between tunnel stretches, and arrive into Kathmandu Central Station’s cavernous underground hall at 8:43AM.

You take the escalator up to the South Exit and emerge on to the front steps of what was once Narayanhiti Palace, gazing on to a broad plaza and Darbar Marg beyond. You stroll along dust-free streets to New Road, take care of business and hop onto the Metro back to Central Station to catch the 12:46PM West-Nepal Express.

After a four-minute ride through a tunnel, the train stops briefly among the high-rise bank and office buildings that long ago replaced the ageing factories and vehicle service centres at what was once Balaju Industrial Estate.

At mid-day the station is quiet, unlike in the mornings and evenings when it is crowded with tens of thousands of people who come by train to work from outside the valley. After several tunnels and quick stops in Bidur, Galchhi, Charaundi and Shaktikhor, you reach Bharatpur at 1:35PM. You finish work in Chitwan and catch the 5:30PM East-West train to Janakpur, reaching home at 7PM.

This may sound like a dream, but dreaming is important for long-term planning.

On 27 August 1893 industrialist Adolf Guyer-Zeller was hiking in the Swiss Alps with his daughter when he imagined riding a train from the pasture at Kleine Scheidegg to the mountain viewpoint at Jungfraujoch.

By 1896 he had permission and financing in place and began construction. The project was completed in 1912 and still brings thousands of daily visitors to Europe’s highest train station, 3,435m above sea level.

Railroads are the backbone of Switzerland’s train network, putting much of the mountainous country (one third the size of Nepal) into commuting distance to the largest city Zurich, while transporting across the Alps tens of million tons of freight a year between Switzerland’s larger neighbours. The country's first rail masterplan was prepared by British engineers in 1850, and big parts of today’s network was built over the next 60 years, at a time when Switzerland’s GDP was comparable to Nepal’s today.

In Nepal, railroads are back in mainstream discourse with the opening of the updated railway from Jaynagar past Janakpur to Kurtha. Nepalis now have firsthand experience of how trains can cheaply transport thousands of people at a time.

While railroads have high up-front costs and need phased construction with long-term financing, they are right for Nepal’s future for a number of reasons:

Electric trains will use clean domestic energy instead of imported fossil fuels.

Railroads carry more people (and freight), faster and more safely using a narrower right-of-way than roads. Railroads thus have less impact on agricultural land, slope stability, and even urban vitality compared to multi-lane roads clogged with traffic.

Travel by train is smoother than by road, allowing passengers to read, write and do other productive activities while traveling, without the risk of congestion delays faced in road traffic.

Trains make it feasible for people to commute daily from 50-150km away, reducing the pressure to migrate to large cities for education and work.

As the world reduces fossil fuel consumption to mitigate climate change, air travel will necessarily become rarer and more expensive, as it does not have ready clean-energy options. Nepal’s neighbours have extensive railroad networks; direct transboundary trains could bring to Nepal large numbers of tourists without relying on air travel.

Nepal’s location between large and growing economies means there is the potential for trans-Himalayan freight trains to partially displace sea-shipping and air freight between the two countries.

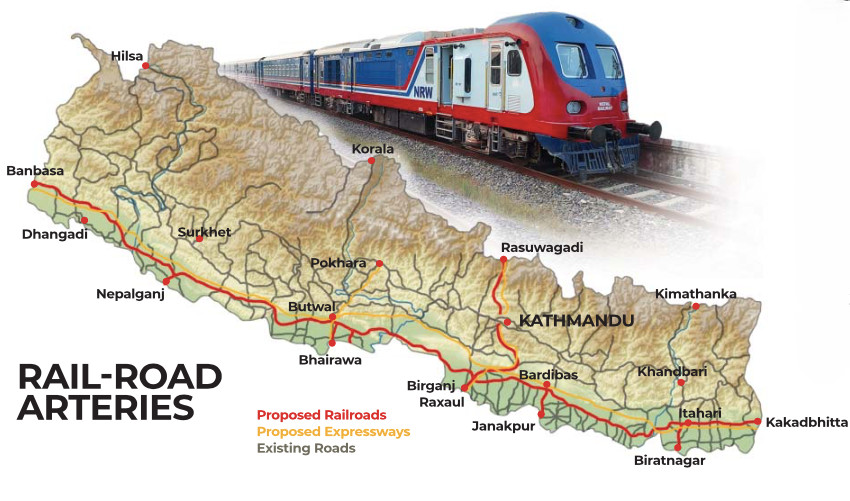

Several potential railroad projects in Nepal are in the pipeline. These include a freight connector from Jogbani border to Biratnagar, expansion of the line from Kurtha to Bardibas, as well as more ambitious projects including a train from Raxaul to Kathmandu, and a train along Mahendra Highway, with side-connectors to Biratnagar, Bhairawa-Lumbini, and Nepalganj.

Most ambitious is the proposal to bring trains from across the Tibetan Plateau to Kathmandu via Rasuwagadi-Bidur, with 98% of the track in tunnels or on bridges.

There have been proposals for possible extensions to Pokhara and Lumbini, but without clarity on alignment. In addition, there have been several proposals for a metro rail system for the Kathmandu Valley.

What is missing from the discourse on individual railroad lines is the longer term thinking of what a 50-year masterplan for Nepal’s network should look like. The individual lines considered so far need to be part of this larger future network, with design decisions for the individual lines based on the masterplan.

Preparing a five-decade Railway Masterplan for Nepal needs to be led by National Planning Commission (NPC) in consultation with stakeholders in Nepal and experts abroad. Several questions need to be addressed early in the master planning process:

First: What kind of ultimate railroad network would address Nepal’s domestic needs in the context of long-term plans for land-use, agriculture, industry and urban growth? Which cities should grow, and what should be their catchment areas? Where should agricultural land and forests be protected (and thus no stations built) and from where will products need to reach the market? Should the east-west railroad connect the towns along Mahendra Highway or run further south? Why?

Should it go through Madi Valley and Chitwan National Park or via Hetauda-Bharatpur? Where should the main interchange between the proposed Raxaul-Kathmandu line and the East-West line be located?

Would it make sense to co-locate it with the proposed Nijgad airport the way Frankfurt and Paris airports integrated long-distance train stations? While many critical questions about the airport project remain, including its exact final location, a direct rail link to Kathmandu would certainly improve the airport’s useability compared to four lanes of traffic jam on a ‘fast track’.

But should the Raxaul line terminate in Chobar, or continue underground to a city centre station as imagined in the opening story? What additional places in Nepal need to be connected to the railroad network? Dhangadi? Surkhet? Dang Valley? Pokhara? Dharan? Are there mountain towns whose access will be easier to maintain via cable car rather than roads? How should the base stations of these cable cars be integrated into the train network?

Second: What kind of a railroad network would meet Nepal’s needs for interconnectivity with the neighbouring countries? Direct trains to Nepal from Indian, Chinese and Bangladeshi cities would enhance tourism in Nepal. There is already a twice-weekly train from New Jalpaiguri near Siliguri to Dhaka. Can the end of Nepal’s East-West trains be connected to New Jalpaiguri to allow direct trains from Nepal to Bangladesh? How would that be negotiated?

Third: What kind of a railroad network would allow Nepal to optimally facilitate and earn from transit trade across the Himalaya? Currently the proposed line from China is expected to descend to Bidur and then to climb up 800m to end in Tokha, north of Kathmandu, while the train from Raxaul on the India border is expected to end at Chobar, south of Kathmandu. This does not allow easy transfer of passengers and freight.

Would trans-Himalayan freight not travel more easily along a track from Bidur to Galchhi and through a tunnel to the Rapti Valley without climbing up to Kathmandu? Or are there other north-south corridors that could work better than the Trisuli Valley, such as Arun Valley?

We also need to keep in mind that freight trains often run at night, when their noise may be un-welcome in larger cities.

Fourth: since our neighbouring countries’ railroads use different track standards, which one should we align with? Most of China’s trunk routes are ‘standard gauge’ with a 1435mm (4’ 8.5”) separation between tracks, similar to Europe’s. Trunk lines in India and Bangladesh use ‘broad gauge’, with a 1676mm (5’ 6”) separation. Janakpur’s existing train is broad gauge.

Given the larger number of potential border crossings to India, does it make sense for Nepal to use broad gauge throughout most of its trunk network, allowing direct trains from cities in Nepal to India and Bangladesh? Then, how far into Nepal should China’s standard gauge line come?

That is partly determined by where there is enough space for a transfer station where cranes lift shipping containers between Chinese and South Asian trains, and where tourists coming from China cross the platform to board Nepali, Indian and Bangladeshi trains. Does Bidur have space for such a station?

If so, we could have a broad gauge line coming up from Nijgad to Kathmandu, passing under the city, descending to Bidur and then heading southwest to Galchhi and the Rapti Valley to re-connect with the East-West line, while a standard gauge line runs north from Bidur.

Fifth: Where do we need to learn from? Engineering challenges and costs increase greatly when trains leave flat open areas to run through mountains or under cities. Design decisions can have large impacts on cost, durability and usability.

Before we invest in construction, it is important for us to learn from the experience and expertise in other countries. While discussion have started with India and China, it will be particularly worthwhile to learn from Japan’s experience in building and maintaining railroads in steep terrain with frequent earthquakes.

It will be important to learn from Austria and Switzerland about how they manage transit freight trains. And learn from the experiences of European cities on how to build effective intermodal connections that tie together urban and long-distance transport while maintaining and enhancing the vitality of historic cities.

In addition, it will be worthwhile to study the financing models used in more recent railroad projects in Kenya, Ethiopia, Thailand and Laos.

Designing and building a national railway network will require longer-term planning than we are used to in Nepal. The leaders who plant the seeds today may not even be alive by the time the investments bear fruit. But there is no time to waste.

We need a masterplan to guide a phase-wise construction of our railway network in well thought-out, predictable and financially sustainable way. Nepal’s railroads will not only generate employment in construction and operation, but it will also bring efficiency and interconnectivity to Nepal’s economy. They will shrink costs and distances while allowing more people to live at home while working in larger cities.

Arnico Panday is an atmospheric scientist with a broad interest in sustainable development. He chairs the Development Planning and Policy Analysis department of Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP).