Protecting pangolins from being eaten to extinction

They may not be as cute, and do not make headlines like tigers, elephants or rhinos, but Nepal’s pangolins are critically endangered and need as much protection as those better known mammals.

A report released in Kathmandu by Nepal’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation on World Pangolin Day on 16 February warns that two indigenous species of scaly anteaters may soon become extinct if they are not protected from poachers smuggling them to feed a growing demand for pangolins across the northern border in China.

“It is very difficult to spot a pangolin in the wild or its burrows when I go out in the field for research nowadays. You really need to be lucky. This wasn’t the case 10 years ago,” said Tulshi Laxmi Suwal, who is doing a doctorate on the mammal.

Titled Pangolin Monitoring Guideline for Nepal the report released on Saturday is a world first – providing instructions on how to monitor the animal’s activity in the wild so action can be taken to protect them.

‘The geopolitical situation is such that Nepal not only acts as the source site but as a transit point for pangolin trade,’ states the report, which its authors hope will help develop a national-level conservation, protection and monitoring strategy.

Pangolins with their armour-like scales are known as ‘living fossils’ because the hardy species have been around for 80 million years. It is also the most trafficked mammal in the world, accounting for 20% of all illegal wildlife trade.

Every year, 100,000 pangolins are smuggled live into China from Southeast Asia and Africa. One million of the animals have been killed worldwide in the last decade alone.

Many Chinese believe the scales have therapeutic value, and pangolin meat is considered a delicacy. Some ethnic groups in Nepal also eat pangolins for their supposed health benefits, but most are now killed or trapped to be smuggled to China.

Nepal is set to become the first country to double its tiger population by 2022, and has marked zero poaching of rhinos for the last few years. But while these charismatic mammals grab headlines, elusive and lesser-known species like the pangolin are being hunted nearly to extinction.

Nepal is home to two species of pangolins: Chinese pangolins have a darker body small head and lack external ears, while Indian pangolins possess brownish yellow scales. Farmers believe the animals to be inauspicious, and they are usually killed if seen.

Chinese pangolins are among the most endangered of all anteater species. Both pangolins are in Nepal’s protected list and killing, poaching, transporting, selling or buying the scaly anteater is punishable with a Rs 1 million fine and/or up to 15 years in jail.

Last year, the Nepal government prepared a comprehensive Pangolin Conservation Action Plan. But more worrying is that Nepal is becoming a conduit for smuggled pangolins from India and Africa to China where the scales are worth $3,000 per kg. A live adult anteater can sell for anything up to $8,000 in China.

In the last five years, Nepal Police have arrested 34 smugglers and confiscated 125kg of scales, four live anteaters, and one carcass and four sets of pangolin skin. In 2016, Suwal identified one of the seized pangolins to be from an African species.

The pangolin trade is flourishing despite the global ban, and smuggling is so rife that of the eight species found in Africa and Asia, four are listed as vulnerable, two as critically endangered and two as endangered.

Pangolin fetus, scales and blood have been ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years, but growing affluence in China means demand has increased. Stuffed pangolins are sold as souvenirs, and body parts are also used in ornaments and even to make bulletproof vests.

“It is essential to also address the ever-increasing demand for pangolin products when talking about its protection,” added Suwal, who is currently pursuing PhD on the anteater in Taiwan, the only country in the world where pangolin population is increasing. “Taiwan is proof that China can also reduce its demand for pangolins through education, stricter laws, transboundary collaboration and enforcement.”

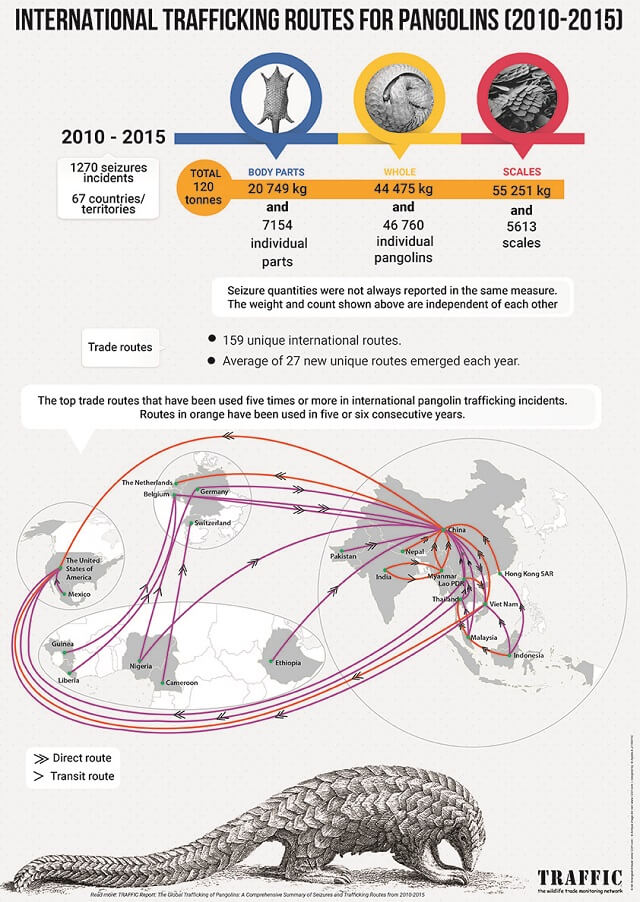

In the recent years pangolin scales are finding their way from China to Europe and the US. A 2017 UNEP report shows that pangolins and their parts have been seized in 67 countries, highlighting the growing global nature of the pangolin trade. (See map above.)

The report found smugglers were using 27 new global trade routes. Europe, especially Germany and Belgium, was identified as a major transit hub and Netherlands was found to be a destination for pangolin body parts and scales from China and Uganda. Hong Kong is a major wildlife trade hub because of its proximity to Mainland China.

Sagar Dahal of Nepal’s Small Mammal Conservation and Research Foundation says some ethnic groups eat pangolin meat, but the animal is under threat now mainly from poachers supplying the animals to China. Pangolins eat termites and ants, keeping a check on the population of these insects, which harm crops and vegetation.

Says Dahal: “For a long time, we have focussed exclusively on saving tigers and rhinos, it is urgent that we also look at protecting pangolins which are now critically endangered.”

writer

Sonia Awale is Executive Editor of Nepali Times where she also serves as the health, science and environment correspondent. She has extensively covered the climate crisis, disaster preparedness, development and public health -- looking at their political and economic interlinkages. Sonia is a graduate of public health, and has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Hong Kong.