Nepalis picking berries in Scotland

Opportunity to earn money as seasonal workers, and to learn new farming techniques

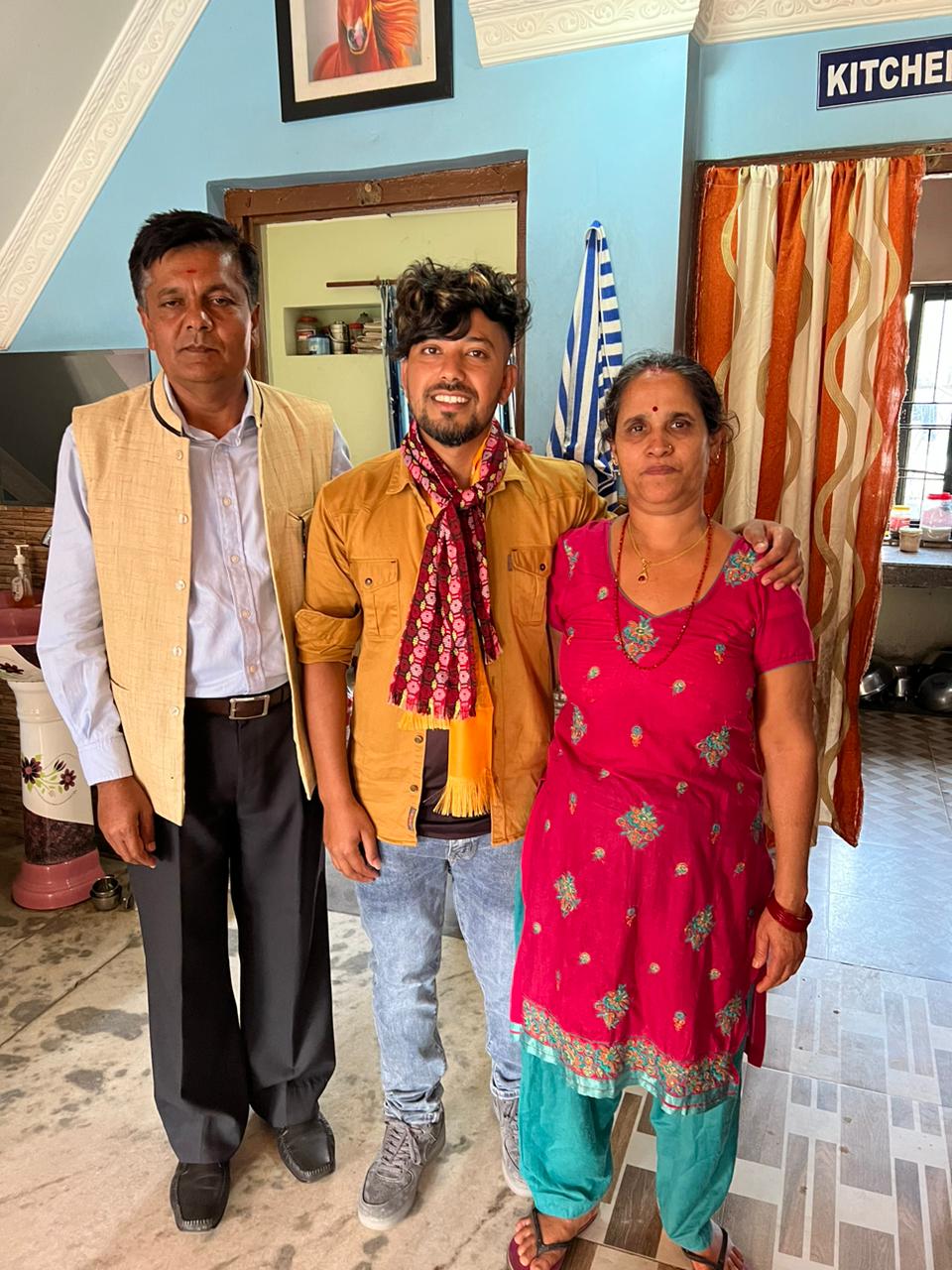

I recently returned from the United Kingdom, where I worked as a seasonal agricultural worker (pictured) for a little over five months.

The idea of going to Britain to work was very appealing, of course, and when a friend made it successfully there, it gave me hope that this was actually a feasible pursuit.

I followed, but faced several bumps along the way that often made me lose all hope. There were lockdowns because of Covid-19, and Nepal being listed in the Red Zone in the UK. But despite the delays and uncertainty, it all worked out in the end.

Read also: Nepalis in the garden of England, Joy Stephen

As anticipated, my job in Scotland was to pick all kinds of berries: strawberries, blackberries, blueberries and raspberries, you name it. In the beginning I enjoyed eating them, but I quickly got sick of eating berries.

My days started at 6AM, but we did not have set work hours and were paid by the amount of fruit we picked and not by the time spent picking them. Picking berries from the ground is significantly harder than picking table-top berries, as I learnt quickly.

We found new ways to pick and sort the fruits faster. The work could get monotonous, of course, but the thought of earning in GBP encouraged us — the more we picked, the more the earnings. The most I earned in a single day was £143, but the average was more like £100 daily. Living costs and tax deductions reduced my savings a bit.

I stayed in a caravan on the farm with other Nepalis. We were from the far corners of Nepal, and all met up in Scotland and became good friends there. There were also Romanians, Ukrainians and Bulgarians on the farm who were more experienced berry pickers than us. Brexit and Russia's invasion of Ukraine has made British employers look elsewhere to countries like ours for farm hands.

I made Tiktok videos to record my experience, and organically started collecting followers who relied on me for information about the application process and life in the UK. The craze to work in Britain among Nepalis, the confusion around the application process with untrustworthy recruiters, and curiosity about farm life in the UK meant people had tons of questions.

I could not reply to people individually, but made these Tiktok videos to address common questions after extensive research on the application process — especially in bypassing intermediaries after a couple of unsuccessful encounters. My experience was useful for other Nepalis who wanted to work in Britain.

I am happy that many benefited from the information I provided, and were able to avoid getting cheated by recruiters.

Read Also: Speaking the language of overseas work

Work in the UK is a good opportunity for Nepalis if malpractices in the recruitment process as has been reported in the international media are addressed so that it is more transparent. Nepalis are relatively new in this seasonal agriculture sector in Britain that has been dominated by Eastern Europeans, but there could be real benefits for us in the future.

My employer asked me to contact him again in February, so I plan to reapply. This is something that Nepalis need to understand: if we honour our contract and work hard it can increase the opportunity to be rehired in the UK. It could even increase the British quota for Nepali workers.

I got to travel around Britain, and managed to save £7,700. But we have to be both physically and mentally prepared to work as farm workers. Many Nepalis who go to the UK have never done physical labour before. Some may expect a glamorous life in Belayat, but agriculture is hard work. It is better if people know that so they don’t have unrealistic expectations and are disappointed.

This was not the first time I have gone abroad to do physically taxing work, so I was both mentally and physically prepared for the UK experience.

Previously, I worked in South Korea under its Employment Permit System (EPS) in the manufacturing sector, first to make carton boxes and then to manufacture tapes.

I had to carry out different tasks as a packer, stitcher and eventually a machine operator. The South Korea bhoot got hold of me soon after I finished my 12th grade, and I was determined to follow many village dais to take that route.

I did not study as hard for the Korean exam as others, but even then I passed easily. I did not go to college and worked in Korea for four and a half years. I could have stayed longer, but chose to return to Nepal.

With my savings from Korea I bought some land, improved my living standard and the stint instilled in me strong work ethics. Until the UK opportunity came along, I ran an electronic shop in Gongabu where I repaired mobile phones.

I had originally wanted to study IT but couldn’t afford it given my family background. In Kathmandu, I took a three-month course in phone repairs. My Korean experience made me more mentally prepared for agricultural work in the UK than other first timers.

I did not pay much attention to learning the technical aspects of farming in Scotland. I was there just to pick berries and make some money. A lot of others there were like me. Nepalis who work on the farm back home will find the job on the farm easy. But they have to be given the opportunity and need support to navigate the complex recruitment system.

I focused only on picking berries, but if there are Nepalis curious and passionate about learning agriculture methods to apply them back home, they can learn a lot from the experience.

Given the demand for UK-based jobs in Nepal, and with the complicated recruitment process, and unethical behaviour of middlemen, the work is beyond the reach of most poor farmers in rural Nepal.

It requires contacts of recruitment agents, ability to use the internet, understanding English, among other things. But the kind of seasonal agriculture experience I got could be even more transformational for the poorest farmers of rural Nepal if there was a farm-to-farm transfer mechanism. They would be even more physically and mentally suited for the job. Furthermore, they would return with experience and exposure to new ideas they could apply back home.

Translated from a conversation with the author. Diaspora Diaries is a regular column in Nepali Times providing a platform for Nepalis to share their experiences of living, working, studying abroad.