A tall order

A white-coated nurse holding a blue and white, half-litre bag of milk stands in front of a small group of mothers seated near the entrance of the Nutrition Rehabilitation Home in Kathmandu.

She is explaining the importance of feeding milk to their children, who are lolling on their mothers’ laps. On a table behind the nurse are containers of pulses and legumes and leaning against the wall, charts displaying leafy vegetables.

But later, listening to the women’s stories, it is apparent that solving their children’s problems will require more than a healthy diet. Through tears, Chandra, 24, says she brought her son Raju, 21 months, to the Home after a routine hospital check-up found that he was malnourished.

His father, who Chandra was forced to marry, bought barely enough food for them to survive, says the woman. That deprivation, plus physical beatings and “mental torture” caused Chandra to flee their village home for Kathmandu.

Mother and son arrived in January at the 24-bed facility perched on a hill on the outskirts of the city, where housing colonies sprout on former farm fields. In the month since then, Raju has gained 1kg in weight and is much stronger.

The boy will stay at the Home for a few more weeks, says Sunita Rimal, coordinator of the Malnutrition Prevention and Treatment Program at the Nepal Youth Foundation, which runs the Home. By then she hopes to have found some work in Kathmandu for Chandra via her informal channels, so that the mother-son pair don’t have to go back.

Epidemic of hunger

Nina Parajuli, 45, brought her daughter Anushka, 7, to the Home weeks later on the advice of staff at a local non-governmental organisation. Nina had gone there for skills training after losing her house-cleaning job in Kathmandu.

She was forced to find work unexpectedly after Anushka was born, when her husband deserted them. The family that hired her ate their first meal of the day only in the afternoon, which meant the girl left for school in the morning having eaten only snacks, while her mother worked. Eventually, Anushka grew dangerously thin and was considered severely malnourished when she arrived.

Nina “was too concerned with her own problems to notice,” Rimal explains. Like her husband, she is HIV positive. She also has a heart condition and is on a waiting list for a uterus operation.

Though unique, the stories of Nina and Chandra share a common thread — the causes of their children’s malnutrition are multifaceted. Rimal says that is the norm: “Most of the people who come here have other socioeconomic problems.”

Past achievements

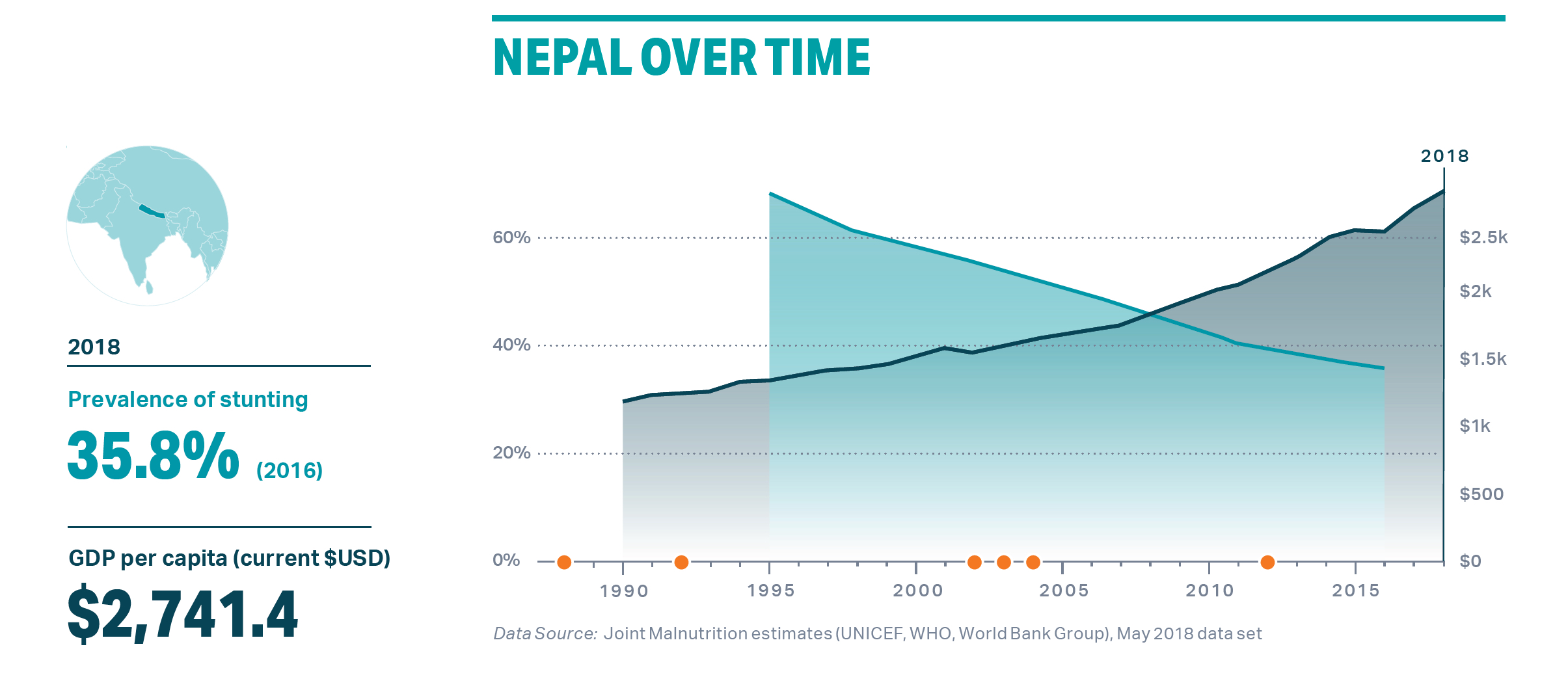

Nepal is celebrated globally for its success in fighting malnutrition from the 1990s until recent years. Most notably, rates of stunting (low height for age) fell from the world’s highest, 68% in 1995, to 36% in 2016.

New research has teased out exactly which development efforts had what impact on stunting. Indirect (also known as ‘nutrition-sensitive’) approaches were surprisingly effective. For example, better educated parents accounted for 25% of the improvement, environmental factors like building more toilets contributed 12% and economic growth made up 9%.

Direct (‘nutrition-specific’) efforts included: improved nutrition of mothers (accounting for 19% of the gain), and maternal and newborn health care (12%), according to the research, published on the website Exemplars in Global Health.

“The exemplars that we picked were countries that did (development) much faster than others. Nepal is not necessarily the best example but it is an important example,” says Zulfiqar A Bhutta of the Centre for Global Child Health at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, one of the leaders of the research.

“One thing is very clear, no one country has done it alone by only investing in health and nutrition sectors,” explained Bhutta via Zoom from Toronto. “And no one country has done it alone by only investing in poverty alleviation strategies. So the truth is that you have to do both in combination.”

Nepal has continued that broad approach, investing in health both directly and indirectly, yet the progress has plateaued.

While stunting continues to fall, the 36% rate is greater than the developing country average of 25% and the Asia average of 21.8%. In fact, the country is on target to hit only one of its nutrition goals for 2025 set by the World Health Assembly — for underweight children under 5 — says the Global Nutrition Report 2020.

So what happened?

“The one thing that I was surprised by is that inequity has increased,” says Bhutta, “and I have a feeling some of that may have had to do with the urban poor or rural to urban migration.”

Nepal, he adds, should work to pinpoint the who’s and why’s of poverty, but otherwise, it should maintain its balanced approach.

Investment on nutrition

A recent analysis from UNICEF found, however, that spending on indirect approaches to fight malnutrition was rising while declining for direct interventions. This goes against the direction given in the government’s Multi-sector Nutrition Plan (MSNP), the blueprint for tackling malnutrition.

Hunger for governance, Editorial

The first phase of the MSNP ran from 2013 to 2017, and the current plan ends next year. The analysis in UNICEF’s Nutrition Sector Budget Brief also pointed out that the cost of programs in phase two (Rs48.9 billion) of the multisector plan is just 54% of phase one (Rs88.5 billion). In addition, the gap between budget numbers and actual spending has been growing.

Kiran Rupakhetee of the Good Governance and Social Development Division at the National Planning Commission secretariat, helped shape MSNP-II. In an online interview he suggests that rather than the current plan’s budget being too low, the budget for MSNP-I might have been “over calculated at the time”.

As to the growing gap between allocations and real spending — it results from many factors, including “rigidities and structural barriers” in the system, he explains.

Another major challenge for MSNP-II is federalism, which introduced three levels of government after elections in 2017. “It’s a Herculean task… because at the moment it’s not only one government—we have 761 governments… There are some difficulties in ensuring coordination among them,” adds Rupakhetee.

The pandemic challenge

The Covid-19 pandemic has added to the challenge. “It definitely has hampered our activities,” says Rupakhetee, “but we tried our level best to keep the programme going.”

For example, parents were trained to measure the arm circumference of infants to detect signs of malnutrition, a task usually done by female community health volunteers, who have been unable to do so due to frequent lockdowns.

Nepal’s school feeding programme was also modified because of the pandemic, with food rerouted to students’ homes, says World Food Programme (WFP) Country Director Jane Pearce, in an online interview.

“Whereas most of the world stopped all of their school meals programmes, Nepal has continued, which has meant that we’re maintaining the nutrition that we’re providing through our locally-managed school meals programmes by giving households take-home rations,” she said.

WFP has also teamed up with UNICEF and other UN agencies to press the government to expand its malnutrition treatment to include not only children who are severely wasted (low weight for age) but moderately wasted, says WFP’s Head of Nutrition Anteneh Girma.

“With the impact of Covid and others, if they’re not treated they will become severely malnourished, then chronically malnourished, or stunted,” he adds.

In June this paper reported on how severe malnutrition was killing children in the poorest communities in Nepal’s eastern plains. It told the story of Raju Devi Sada, whose first daughter died at 3, after being malnourished. A second daughter died soon after birth, a year later.

A third daughter is underweight and local health workers have recommended feeding her nutritious food. But Raju Devi cannot afford vegetables, eggs, milk and meat, and what she earns as a daily wage labourer is barely enough to feed the rest of the family.

“We have found that up to 70% of children who die every year in Province 2 do so due to malnutrition, and the main reason for that is extreme poverty,” said Kedar Parajuli at Nepal’s Family Welfare Division. “Without alleviating poverty, we can’t solve malnutrition.”

WFP is doing mapping, using mobile data, to create what it calls a vulnerability index. It documents people’s access to water and sanitation services, health and other factors, in addition to nutrition, says Girma.

He adds, “Our nutrition response, food security response, is informed by that index… it indicates those who are vulnerable for not having access on time, for being exposed to various inequalities.”

The private sector

Girma points out that WFP, both in Nepal and globally, supports the multisector approach. In that vein, the UN agency is working closely with the government to establish the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Business Network in Nepal. To date, 10 companies, all working in the food industry, have become members.

Ending malnutrition and other food-related diseases “will happen only if the private sector is responsible for what they are producing, and producing something safe … so their engagement, bringing them to the table, is very important,” says Girma.

Leading collaboration with the private sector on the ground is Baliyo Nepal, a non-profit company that generated headlines when it launched in 2019. The initiative was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the Chaudhary Foundation, the charity arm of the Chaudhary Group, makers of Wai Wai instant noodles, which are widely considered junk food.

Junk food is making Nepali children shorter, Marty Logan

Today Baliyo Nepal is set to expand a pilot project that has been running in Lumbini Province since 2020 — raising awareness about nutritious food among school children, including via a cricket program, and educating shopkeepers to sell the nutritious foods in the first phase of its ‘Baliyo Basket’: eggs and a single-portion Rs10 sachet of fortified porridge for infants.

“Seventy percent of the sachets in the market were sold, according to the sales report,” says Baliyo Nepal CEO Atul Upadhyay, a nutritionist, in an interview in his Kathmandu office. “The feedback we’re getting from mothers is ‘Now we want it in a bigger package. We can’t go to the shop every day and buy the Rs10 package’.”

Upadhyay says manufacturers will start making the larger packs by year end. That is just one of many plans he is cooking up — besides expanding pilot activities to Bagmati and Gandaki provinces, the company will soon be adding to its Baliyo Basket a fortified drink for pregnant and lactating women and fortified porridge for 2-5-year-olds, once they are approved by the government.

Upadhyay notes that both the government and private sector are gradually embracing his innovative approach but stresses that new ways to fight malnutrition, like this public-private partnership model, are essential if Nepal is to reach its nutrition targets.

“It’s not important who works for nutrition. It’s important that someone works for nutrition, whether it be WFP, Baliyo Nepal, company A, company C — I don’t mind,” he adds.

Target Stunting

Stunting, low height for age, is a sign of chronic undernutrition. It can hinder brain development resulting in reduced mental ability and learning capacity, poor school performance in childhood and lower earnings and higher risks of nutrition-related chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension and obesity, in adulthood.

Nepal cut its stunting rate dramatically in recent decades, and it is one form of malnutrition that the country might be on track to reduce in line with coming targets: MSNP-II (2022), World Health Assembly (2025) and SDGs (2030).

The UNICEF Nutrition Sector Budget Brief says that the average yearly rate of stunting reduction since 2001 (3.25%) must increase to 3.8% to meet the MSNP-II and WHA targets, and rise to 6.5% to meet the SDG target.

According to Kiran Rupakhetee at the National Planning Commission: “The Nepal Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey has brought some encouraging results, but it may still be difficult to make the WHA target... but since the SDGs deadline is quite far away I’m very much optimistic and hopeful that we can meet it.”

Stunting rates and targets

2016: Nepal Demographic and Health Survey – 36%

2019: Nepal Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey – 31.5%

2022: Target: Multi-sector Nutrition Plan-II – 28%

2025: Target: World Health Assembly – 25%

2030: Target: SDGs – 15%

writer